Blog post - A feather at a time

01 Jun 2021 Philipp Boersch-Supan citizen science Tweet this!This blog post was originally published in the BTO’s Lifecycle magazine

Most adult birds moult all their feathers once a year, which provides an energetic challenge on a par with reproduction and migration. Despite this, moult has been a neglected subject in ornithology and much remains to be learned about how it fits into the annual cycle of birds. Here I highlight the value of recording scores of individual primary feathers.

Documentation of basic moult data such as the timing, location, sequence, and completeness of feather replacement is crucial for any attempt at unravelling the physiological and environmental causes of moult and how these might differ between species and regions. As changing climates alter birds’ breeding and migration seasons, how is the timing of moult changing? Ringing records provide a critical source of information and we have been looking at how we can best make use of them. Specifically, we are interested in quantifying the variation in passerine moult timing and duration, and investigating potential environmental drivers thereof. Estimating the date when moult starts and how long it lasts in wild bird populations is challenging; usually the full progression cannot be observed in individuals. Rather, we have to infer moult timing across a population from snapshots of different individuals throughout the season that are usually only caught once.

RECORDING MOULT

One of our first insights from this

project is that the way moult is recorded

matters. The guidelines in the Ringers’

Manual allow two types of moult

information. Moult codes consider

moult progression across the entire

bird in broad categories relevant to all

ages, whereas primary scores track the

progression of flight feather moult in

more detail.

SIMULATION

To determine the relative value of these

two approaches, we simulated moult in

a large virtual population of adult birds.

We then sampled this virtual flock as if

we were catching them using different

levels of effort (i.e. numbers of birds

caught over the course of a season) and

noted either the moult code (‘O – old

plumage’, ‘M – active main moult’,

‘N – new plumage following main

moult’) or the scores of the individual

feathers for each (0–5). Finally, we used

a statistical model to estimate moult

timing for each sample. Because we

know how moult progresses in our

simulated population, we can assess

how accurate our statistical estimates

of moult commencement and duration

are using the two recording methods.

Estimating moult dates and

durations is sensitive to when birds are

observed in their moult cycle. Ideally,

records from a season cover birds in

all stages of active moult as well as

those individuals that haven’t started

(code ‘O’, score 0) and those that have

finished (code ‘N’, score 50). We found

that this was particularly important

when using moult codes alone.

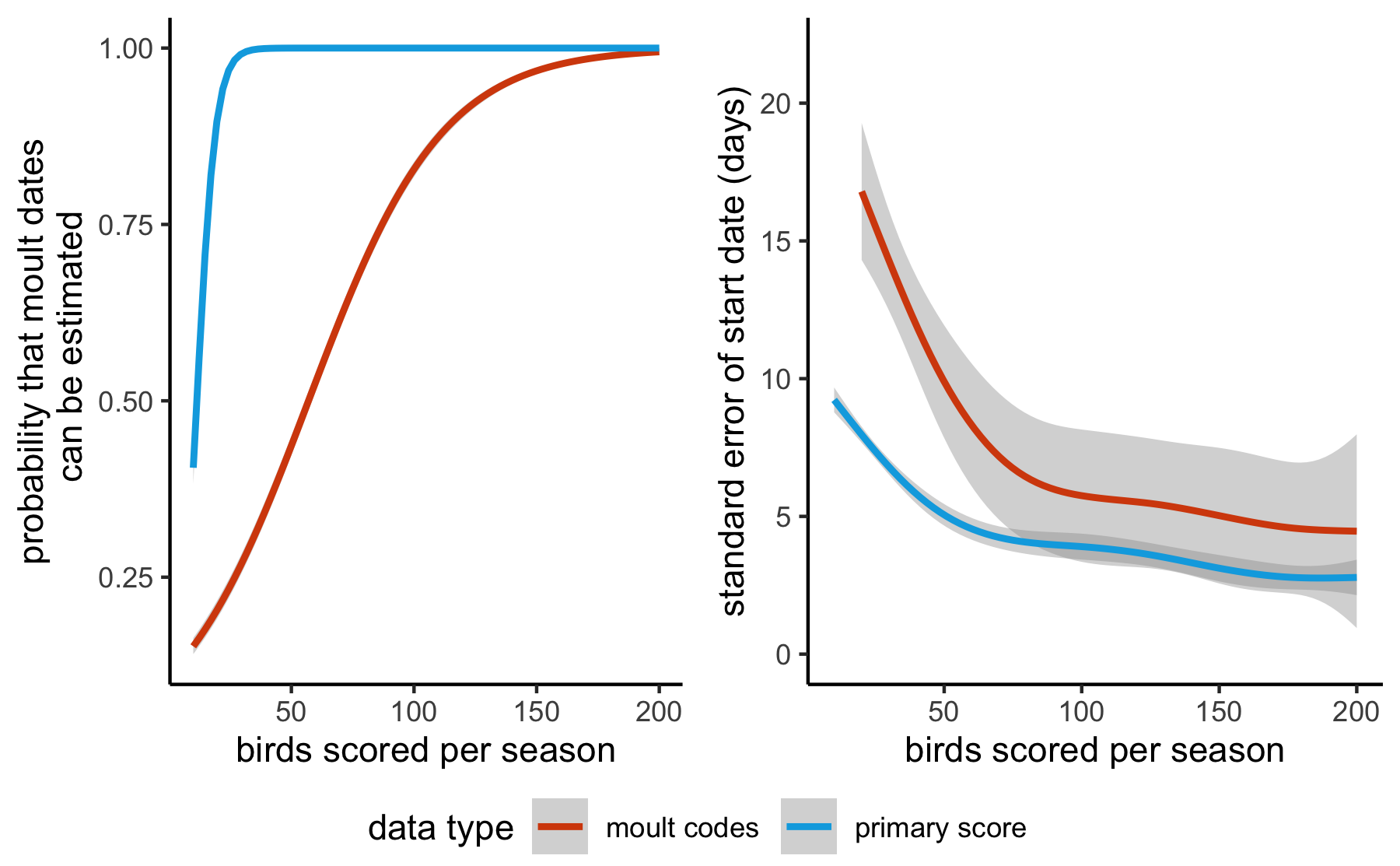

Analyses of moult timing (phenology) based on primary scores require a much smaller sample size to yield useful results (left), and deliver date estimates with higher precision, particularly for small sample sizes (right).

RESULTS

On average, a much larger sample of

birds with just a moult code is required

for the phenology model to yield any

results – 50 birds sampled randomly

across the season offers only a 50:50

chance of successfully estimating

moult start date and duration (see

graph). Primary scores hold much

more information, because wing moult

progresses in a near-linear fashion in

many passerines. A random sample

of about 30 scored birds virtually

guarantees reliable estimates of moult

phenology. Further, when estimation

succeeds, the estimated dates and

duration are much more precise for a

given sample size when using primary

scores.

Samples larger than c. 50 individuals

with primary scores yield standard

errors smaller than about five days. For

moult codes, a threefold larger sample

is required to obtain the same level of

precision. Although these numbers

might seem small in a national context,

by the time you start breaking the

sample down by sex, habitat, location…

every record becomes valuable. So, next

time you are processing captured birds

please consider recording a full set of

primary scores, and remember, scores

of pre- and post-moult birds are as

important as those of actively moulting

birds to understand the phenology of

feather replacement.

REFERENCES

Underhill, L. & Zucchini, W. (1988) A model for avian primary moult. Ibis 130, 358–372. DOI

Boersch-Supan, P. et al. (2021) Bayesian inference for models of avian moult timing. Poster presented at EURING 2021. DOI