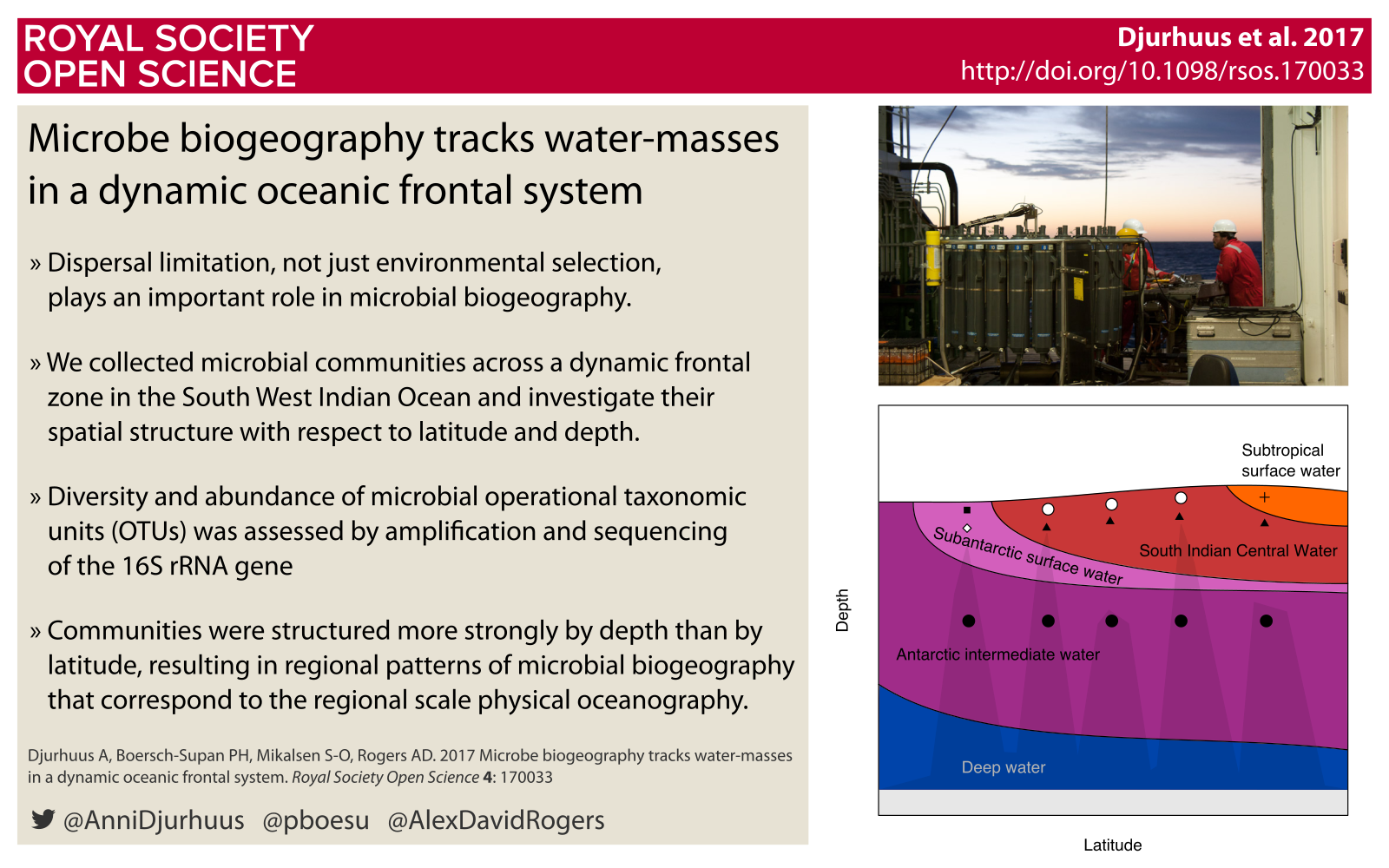

Campbell Island - A life boat in a changing ocean

15 Apr 2017 Philipp Boersch-Supan seabird islands albatross Tweet this!Many populations of sub-antarctic animals and plants are in decline, threatened by an array of direct and indirect human impacts. The restoration and protection of predator-free island habitats is a crucial component of conservation measures to ensure population persistence in a changing world.

In late 2016 I was awarded an Enderby Trust scholarship to visit the sub-antarctic islands of New Zealand. Here are my impressions from Campbell Island.

A bare patch of volcanic rock marks the final climb to the ridge line, then the path disappears in waist high tussock. A startled Campbell Snipe jumps into the air and dashes downhill in erratic zig-zags. We pause for a moment just below the ridge crest, to take shelter from the winds and the drizzle they carry. Strong winds circle the globe at this latitude. Largely unbroken by land they sweep the ocean separating Antarctica from the rest of the world and make the Southern Ocean home to the majority of albatross species. But on this grey morning, there is little activity in the colony on the hill- side. Only when we step onto the ridge crest, white spots become apparent in the tussocks on the hill side. Southern Royal Albatross, huddling on their nests. Some have their beaks tucked under their wings, others sit quietly, inspecting our small group.

A Southern Royal Albatross Diomedea epomorpha on Campbell Island.

It is early in the breeding season and the birds have just begun to lay the single egg that each will be incubating this year. Royal Albatrosses usually only breed every other year, but those that are breeding this year have occupied their nest sites and are guarding them, while their partners are out at sea feeding.

We cross the ridge, leaning into the wind before descending the windward hillside. Tussocks and ferns give way to a meadow of megaherbs. Colourful stands of yellow, purple, and greenish-white flowers. In the midst of it sits a pair of Sub-antarctic Skua. Further down, on the cliffs edge, nestled in between purple flowering stands of Anisotome latifolia. sit the chicks of Giant Petrels. Already the size of a Christmas turkey they are starting to loose their down and are growing their first set of feathers. Beyond them jagged limestone cliffs drop into the sea. A pair of Light-mantled albatross dash along the coast line and out onto the sea. The sooty coloured birds with paler backs and bright white rings around their eyes are performing an airborne courtship dance, each taking turns at leading a synchronised display of flight skills.

Northern Giant Petrel chick Macronectes halli.

Courtship display of two Light-mantled albatross Phoebetria palpebrata.

Tussocks dominate again, then a thick brush formed by grass trees, ferns, and Myrsine divaricata as the path disappears into a steep gully down towards the beach. The track is well trodden - it is a route used by the locals: shy hoiho or Yellow-eyed Penguins commute along it from their marine foraging grounds to their nests which are hidden in the scrub. New Zealand fur seals also wander along here on occasion, usually subadults on the search for unpartnered females.

The cut opens as we reach the shore. A small bay with a pebbly beach covered in strands of bull kelp. Above the tide line a massive hunk of blubber. A Southern Elephant Seal bull, hauled out here to moult. Behind him a handful of smaller conspecifics, most of them juveniles, recently weaned from their mothers.

Our hike across the island has revealed rich plant and animal communities, and it would not be far fetched to think that this wild island is a pristine outcrop in the Southern Ocean. Yet, over the past 200 years humans have left their mark: Sealers almost completely eradicated the local fur seal population in just a few years after Campbell Island was discovered in 1810. Whaling followed, then the establishment of a pastoral lease. Human activities introduced not only cattle and sheep on the island, but with them also predatory mammals such as rats and cats. The consequences were disastrous: Rats and cats were literally eating the local birds, extinguishing the unique Campbell Island Teal and Snipe on the main island.

Rats - together with feral live stock - also decimated the unique plant life on the island. Even after the sealing and whaling had ceased, the pastoral lease had been given up, and Campbell was declared a nature reserve in 1954, the introduced mammals continued to wreak havoc on the island’s ecosystem. The deadly combination of human exploitation and introduced predators was not just a problem for Campbell. Most sub-antarctic islands have been altered by the same or similar human impacts.

A Campbell Island Snipe Coenocorypha aucklandica perseverance in a Bulbinella stand.

Luckily for Campbell, all was not lost. As the result of decades of conservation work the island is slowly regenerating. Sheep were successively excluded from the island starting in the 1970s, and completely removed in 1991. Cattle were removed in 1987, and the cats died out for unknown reasons sometime before the 1990s. The rats persisted, however, and it was not until 2001 that they, too, were eradicated. The rat eradication, undertaken by spreading poisonous cereal baits from helicopters, was the largest ever attempted at its completion, and set an enormously successful example to more recent and ongoing eradication programs around the globe.

Since the eradication, the plants and animals on Campbell are regenerating. Seabirds returned, the Campbell Island Snipe and Pipit recolonized the island from remnant populations on rat-free outlying islets, and in a serendipitous twist, the Campbell Island Teal - thought to have been driven to extinction by cats and rats - was rediscovered in 1975 on Dent Island, an islet in Campbell’s Cattle Bay. Captive breeding ensured the survival of this species, until it could be successfully reintroduced to its home following the rat eradication.

The plants are regenerating as well. Megaherbs now form colourful fields on the hillsides, providing Spring time visitors with a re- markable scenery, while strict regulations ensure that human visitors do not harass the wild life or bring new unwelcome plants or animals to this sub-antarctic jewel.

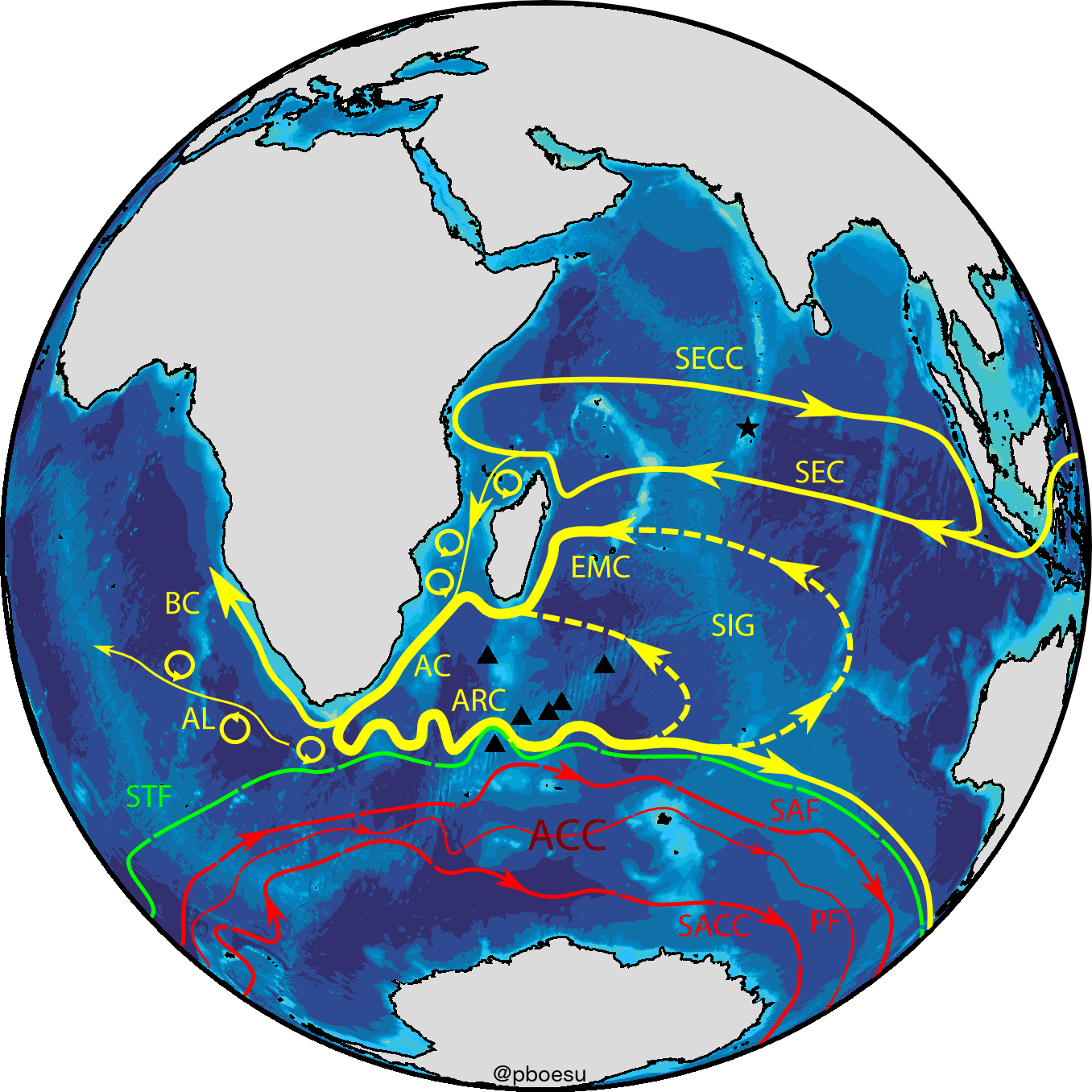

All well that ends well? one could ask at this point. Sadly, further conservation and protection measures are necessary. Restoring and protecting island habitats is necessary to safeguard sub-antarctic species, but not sufficient for all of them. Seabirds and seals do not live on islands alone, they are true ocean wanderers, covering vast distances in the polar oceans. They are at threat from bycatch in fisheries beyond the reserve boundaries, and from pollution. And both on and off the islands, all species are feeling the impacts of a changing climate. Temperatures are rising, rainfall and wind patterns are changing, as are ocean currents and the food they carry. Scientists still have an incomplete understanding of the effects these changes will have on the animals and plants of the Southern Ocean, but it is clear that to mitigate the effects of climate change we must strive to remove as many other stressors as possible from wild populations. Restored and strictly protected islands like Campbell are life boats in a changing ocean, but to make them as effective as possible we also have to work harder to eliminate fisheries bycatch of vulnerable species, and to greatly reduce the amounts of plastic waste and chemical pollutants we release into the oceans.

It is afternoon as we make our way back to Perseverance Harbour. The clouds have parted slightly, and buoyed by a steady breeze more and more Royal Albatross return to the island. With their massive wingspan they soar over our heads as they pick out their partners on the hillside. Once reunited, pairs greet each other and engage in mutual preening. Elsewhere, groups of juveniles are busy socialising. In a behaviour known as gamming they form small circles, where they take turns in an astonishing display: One at a time, they call towards the sky, wings outstretched and head and neck stretched upward. They croak, they yap, they clasp each other’s bills and shake their heads. A magnificent and touching display at once.

A sky-calling Southern Royal Albatross.

Eventually we move on, albeit reluctantly, to descend through tussock and scrub until we reach Garden Cove. Pipits sing from the flowering Dracophyllum grass trees, and terns shriek as they hover over the shallows. As we return to the Spirit of Enderby, our cameras filled with images and our heads with memories, a lonely Sitka spruce remains back on shore. Over a hundred years old, and thousands of miles away from its species’ home range in North America, it is a poignant reminder of the long human history on Campbell, and our meddling with the island’s ecosystem.

Philipp Boersch-Supan is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Florida. He studies the ecology of albatrosses and other animals of the open ocean. His trip to Campbell Island was made possible through the generous support of the Enderby Trust.